Rob is fascinated by Ancient Roman history. A magnificent society with an empire that sprawled across entire continents and then collapsed. Emperor Claudius ordered the first major Roman invasion of England in 43 AD and by 50 AD the Romans controlled most of England. In 122, rather than conquering the wild north British tribes, Emperor Hadrian built a coast to coast barricade. At 73 miles long, this was one of Rome’s greatest engineering projects. We had to see it.

Housesteads Roman Fort

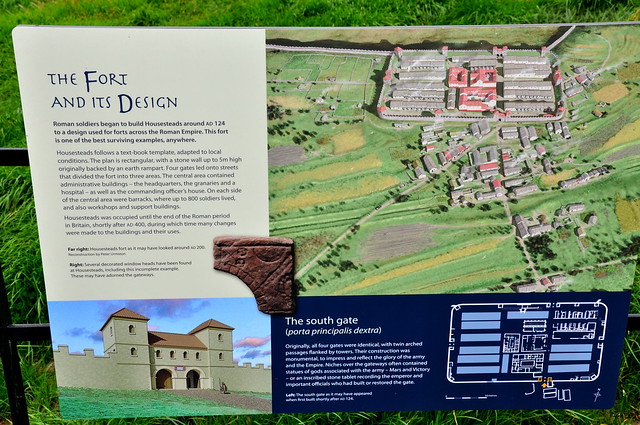

We drove up for a long weekend when Rob’s parents were visiting to walk some of Hadrian’s Wall. I chose a big circular walk that went past 2 excavated Roman forts and the most well preserved stretch of Hadrian’s Wall. The walk starts at Housesteads Roman Fort. It’s listed as the wall’s most dramatic site and the best preserved Roman fort in the whole country. Neat! Roman soldiers began building Housesteads around AD 124. Roman soldiers often built their own forts, and all had trade skills that would be used in the fort as a settlement. You can see the remnants of the fort up on the ridge in this picture.

Outside most Roman forts was a settlement, called the vicus, which was full of civilians. The civilians and soldiers would engage in trade, leisure and worship together. Soldier’s sweethearts and families would also have lived there. Apparently, soldiers sons would often become solders themselves – essentially becoming Roman without ever visiting Rome. I’m standing outside a building what was identified as an inn.

The fort design is very typical, rectangular with four gates in the 5m high stone wall (well, not 5m high anymore). The central area (red in the picture below) contained administrative buildings – the headquarters, a hospital and the commanding officer’s house. On each side of the central area were barracks, where up to 800 soldiers lived. The soldiers would’ve come from different corners of the empire, including Spain, Belgium and Norway. It would’ve given the fort a very international feel.

The commanding officer’s house was residence for him, his family and a number of slaves – very lavish for living on the northern most edge of the empire! The building was arranged around an open courtyard, and in the northern part of the house had a heated room (!) which served as a bath suite. It’s kind of hard to see here, but you get the idea.

The hospital is the only example if its kind in Britain. It had four wings around a central courtyard and an ‘operating theatre’ occupying the northern section (closest to the camera). I suppose the Romans wanted all their soldiers healthy and well whether they were fighting or not.

The other great part of the fort was the cleverly ventilated granaries – the granaries had underfloor heating to keep the grain warm and dry even in a snowy winter. The grain would’ve been warmer than the soldiers! The floor sat on top of these stone piles and hot air from a constantly burning fire was blown around. Clever indeed!

We also got our first teasing look at Hadrian’s Wall. It’s much wider than I thought it would be! I suppose that’s why it’s been here for 2000 years.

Hadrian’s Wall

There is a Hadrian’s Wall path 84 miles long that runs the length of the wall from coast to coast. We only looked to do a most a mile or so of the wall based on the map I had downloaded. Apparently the whole walk was going to be 3 1/2 miles. Not too bad. However, turns out the map had a typo…. by the end of our day we had walked 8 miles. Yikes. So we walked at least 3 miles of the wall itself, including all the ups and downs. Even if it was longer than planned, it was a pretty amazing walk.

The wall would’ve been 3 – 3.5 meters high when it was built, but over the years has sunk and had stones stolen by local farmers and landowners. Though now its a Unesco world heritage site, its illegal to vandalise it anymore. Here’s a recreation of how high the wall would’ve been at full height on the right and a lookout tower on the left.

The preservation of much of what remains of Hadrian’s Wall can be credited to John Clayton. He became enthusiastic about preserving the wall after a visit to Chesters in the 19th century. To prevent farmers taking stones from the wall, he began buying some of the land on which the wall stood. Eventually he had control of land which included the sites of Chesters, Carrawburgh, Housesteads and Vindolanda. Fantastic stuff.

The wall had a number of gates, which the Romans could have used as customs posts to allow trade and levy taxation. The gates are called Milecastle markers and are once every Roman mile – about 1,00 paces. We walked past Milecastle 37, 38 and 39 on our walk. Here’s the remnants of Milecastle 38 below.

Vindolanda Roman Fort

After stopping for a well deserved pub lunch and pint, our walk continued on to Vindolanda Roman Fort, our last main site to see. The extensive site gives a insightful glimpse into the daily life of a Roman garrison town. The layout of the walled fort is almost identical to the Housesteads Roman Fort (indeed every Roman fort in the empire…) but what makes the site so huge is the size of the township outside the walls too.

The really impressive bit about the site was the high quality museum (no photos allowed though!) with 2 memorable highlights. First was the surprisingly impressive display of different leather sandals that had been excavated from the site. Some had decorations in the leather and others with soles covered in studs to make them hard-wearing for outdoor work.

The second highlight was the collection of Roman writing tablets – delicate slivers of wood covered in spidery ink writing (here’s an example). The tablets were found in oxygen-free mud on and around the floors of the deeply buried early wooden forts at Vindolanda and are the oldest surviving handwritten documents in Britain. Amazing! The contents of the tablets were so insightful – a student’s marked work (which was ‘sloppy’), a parent’s note with a present of socks and underpants and a birthday party invite from one officer’s wife to another. Wonderful.

It was a great day full of new insights learning about Roman forts, fortifications and settlements at the north-most edge of the Roman empire. The weather was cool but clear – perfect for walking – and the landscape was rolling and refreshing. Great to get out of the city for a while.

A great day, with more to come.